EARTH-SCIENCES EDUCATION IN THE CONTEXT OF SCIENCE-TECHNOLOGY-SOCIETY:

AN ETHICS CHALLENGE

1. INTRODUCTION

The authors assume in this Conference their

professional involvement as science educator researchers. Therefore, this paper

starts with a reflection about the

science education approach in the knowledge society in the context of

science-technology-society (STS), emphasizing the role played by the ethical

dimension of this challenge. Afterwards, a discussion concerning the

contribution of the earth sciences’ curricular topics to the achievement of this issue, takes place.

The authors of

this study recognize that the need for

change in today’s modern knowledge-driven society - in which science plays a relevant role - is generally accepted

as being one of the major challenges at the beginning of this millennium; they

also assume the high level of complexity in the society itself, including the

development of new science teaching context approaches, in accordance with the

suggestions emerging from science

education research. Science education here seen as a wider brief than providing

future professional scientists.

The science teaching context means that science

contents are taught in connection and integrated with the students’ everyday worlds, and in a manner that

mirrors students’ natural efforts at making

sense out of those worlds. In other words, teaching science through

science-technology-society (STS) refers to teaching natural phenomena in a way that embeds science in the technological and social environments of the student. The

intention is to help learners live in democratic countries effectively, and

therefore environmental and social problems

which have evolved in part from the use of science to produce

the technology for the 21st century should and, we believe, will become the major objectives of publicly

supported science.

Within all this framework it seems clear that in a democratic society, with

understandable conflicting voices,

nobody – teachers, students, … - is in

a neutral position as far as the possibility of deciding upon what actions will be most

beneficial for the citizen, for the

society, for the environment and, particularly, for the interaction between all

of them. Nevertheless, to take

decisions, a broad and balanced view about the natural world –

biosphere, lithosphere, atmosphere and

hydrosphere - is needed, and not one only based on the circumstances

which occur at a particular moment. To take decisions does not only depend on the

content knowledge previously achieved;

it is not value free. Decisions

should be taken within an ethical framework, and it is crucial to

recognize the best educational, particularly

science educational, strategy to

construct an information society that

is ethically sound.

Earth sciences and earth sciences education, strongly

linked with the Earth, are exceptional fields to contribute to the

achievement of this dream. In fact the Earth that supports and sustain us, feeds our children and receives our dead,

is the very image of solidarity, and the source of all our productions,

economic or otherwise. Viewed in this

way, the discipline is as much a part

of the humanities as it is science. Alongside the field of sedimentology, hydrology, and economic geology

one should find geopoetry and geometaphysics, geopolitics and

geotheology, geoaesthetics and a geoepistemology (Frodeman 2003, 217).

2. INFORMATION SOCIETY AND SCIENCE

EDUCATION

A few comments about the relationship between science

and technology in a sociological context; this articulation cannot be divorced from an ethics compromise.

It seems to be true

that not to know any

science is to be an “outsider” - an alien to the culture as much as somebody who cannot

recognize the cultural referents

that are a product of the Ancient Civilization, i.e. Greek

Civilization. On the other hand, the idea of technology is in the

discussions’ agenda all over the world.

Nevertheless, the authors assume that the scientific

and technological worlds, despite their idiosyncrasy, are no longer separated in our society. And this strong link has a cultural impact on our thinking and

behavior because it is not possible nowadays to think about the scientific

knowledge out of a technological framework. There is a temptation to start

strengtherning a technological

ideology, meaning that there is a close

relationship between

science/technology and the best solutions we are looking for. This ideology argues that socio-political

and ethical criteria are not very much relevant when one finds a solution for broad current problems,

taking into account that they should only

be overcome from the science/technology

contribution (Praia and Cachapuz, 2005).

Although science is one of the major achievements of

Western civilization, and permeates our culture rather as mica pervades

granite, the pretence that science, technology

and scientists are separate from

society and its applications has been unsustainable. In addition, technologies

are not only tools, but also vehicles of affordances, values and

interpretations of the surrounding reality and, therefore any significant

technology is always ethically charged. So it is understandable that the

construction and development of the triangle science-technology-society (STS)

taking into consideration the correspondent in depth interaction.

The institutions and also the citizens need to develop

an efficient and effective strategy to

deal with the new ethical challenges

arising in the development of the information society. Essentially in

our society, science is moving from a view where it is perceived as a source of solutions towards another

one where it is also seen as a source of

problems. And this is a critical and urgent issue. It is critical

because the international community

feels that it is crucial to get sources

for conceptual and ethical guidance. It is urgent because the information

society is developing at a fantastic pace, and has already posed

fundamental ethical problems, whose complexity and global dimensions are

rapidly evolving. In fact in a few decades mankind has moved from a state of submission to nature, to a

state of power of potential total destruction. In the

present state we have the means

and tools to engineer

entirely new realities, tailor them to

our needs and invent the future. For the first time in history, we are

responsible for the very existence

of whole aspects

of our new environment (UNESCO,

2001). Science and technology, when associated, have an immense power.

Nevertheless our moral responsibility towards the world and future generations

is also enormous. Unfortunately, technological power and moral responsibilities

are not necessarily followed by ethical

intelligence and wisdom. And this tremendous responsibility starts with

scientists themselves … as a first step, they have to become conscious

of the part they play in producing certain knowledge and certain products and the uses to which

they are put; secondly, scientists have to learn to view their work in the context of values and goals that affect it and the ways it affects society. Ethical concerns should include an attitude of reverence

toward human and other creatures,

concern for the safety of products as regard

health and possible impacts on the environment. Also, scientists should

take care to point out benefits

and risks more openly, both in the front of decision

makers and the public. (Sandal 1998). And the same author concludes saying

that these considerations and responsibilities must be part of the scientist’s

education.

Of all the

above, the authors of this paper argue about the relevance of including an

ethics reflection in the scientists

education but also in the educational core curriculum of those who are in the

front line of an education for the citizenship i.e. the teachers in general and

the science teachers in particular. If there is no doubt about the remarkable

role played by science/technology in

the construction of the knowledge society, it is also understandable to argue

that the ethics dimension is essential to strength both a joint and individual conscience which are able to

become the foundation of a society concerned with the effectiveness, solidarity, the environment and the future generations.

How to face this big challenge? Science education has

to be prepared to contribute to this issue, which means to help the learners to

be democratic and, therefore, intervenient citizens. Any consideration of the

role of science education must begin not with an internalist view of its

content and curricula, but rather with

an externalist perception of the society it serves.

The deep changes in the global society, the challenges

raised by the increasing development in

science/technology and, last but not

least, the complexity of current problems have stimulated new ways of

approaching the processes of production and dissemination of

knowledge and the resulting impact on modes of teaching and learning. For

example, learning how to learn, and being able to use what one has learned (for

social reconstruction, perhaps) within an externalist framework is a demanding competence to achieve. And this competence is considered quite

superior to amassing academic knowledge

(Aikenhead, 2002), something quite

close to what is mainly carried

out at the present.

A different approach is needed to develop the kinds of

competencies, knowledge and values that our future citizens are likely to need.

When one thinks about main aims of science education

within this information society there are four arguments emerging from the

literature (Thomas and Durant, 1987; Millar 1996; Osborne 2000). They are the

utilitarian arguments, the economic arguments, the democratic arguments and the

cultural arguments.

The utilitarian and the economic are respectively

strongly related to:

. the fact

that learners and citizens might

benefit in a practical sense from

learning science and

. to the argument

that an advanced

technological society needs a constant supply of scientists to sustain

its economic base and

international competitiveness.

These issues will not be discussed in the context of

this paper. Nevertheless a few comments are conducted as far as the democratic

and cultural arguments are concerned.

The democratic argument is very much related to the

fact that each citizen has to construct his/her own view related, among others,

with the following issues:

. the way scientists work, how they decide that a

particular study is the “right science”, how the controversy and uncertainty

surrounds contemporary scientific research. There is no more room for a picture

of science as a body of knowledge which is unequivocal,

uncontested and unquestioned (Claxton 1997);

. aspects such as global warming, rising sea level,

water resource – sterilization and pollution, soil loss, desertification, waste

disposal, energy and mineral supply, water resources;

. the need of

the recognition that the damage in the

public faith in the expertise of

science is a result of a

misunderstanding of the nature of science;

. that future debates in society will be strongly concerned with political and moral dilemmas;

. taking into account the characteristics of the

problems that mankind is faced with – complexity, uncertainty, systemic

framework, … - the correspondent

solutions have to be reached through a cooperative engagement, rather than an

individual participation.

Therefore a healthy democratic society implies the

participation and involvement of as many citizen as possible looking for the

solutions of the decisions rising from the choices that contemporary science

will present. All of this is only

likely if the citizens have a basic understanding of the underlying science,

and can engage both critically and reflectively in a participatory debate

(Osborne, 2000)

About the cultural argument. There is no doubt about

the fact that science is one of the most important achievements of our culture.

Science, as well as technology, play such an important role in our society, are

deeply linked to our procedures and behaviors, are so strongly connected to our

way of life that, it is understandable

why they belong to the cultural

dimension. There are implications of this on science education. This means that

understanding the culture of science is needed. So it is relevant the pay

attention to the set of issues that follow, such as: the history of science,

science ethics, science argument , and

scientific controversy, i.e., more

emphasis on the human dimension rather than only on the body of knowledge.

3. EARTH SCIENCE APPROACH: AN ETIHCS CHALLENGE

The authors discuss through this section the implications of the previous views in

the context of earth- sciences curricular approach towards the

achievement of a relevant role for

earth-sciences education..

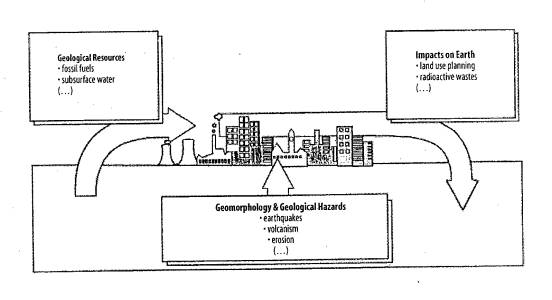

Figure 1 is a useful contribution of Woodrock (1995)

for displaying the relationship between earth-sciences and society. A careful

reading of the diagram helps the reader

understand, as it was previously emphasized, that:

* teaching earth-sciences through STS refers to

teaching natural phenomena in a way that embeds science in the technological

and social environments of the learner (think about fossil fuels related to ethics dimensions);

Fig. 1 Earth

sciences and society (adapted from Woodrock, 1995)

* in a democratic society, with conflicting voices and

interests, nobody is in a neutral position as far as a possibility of deciding

upon what actions – concerned with subsurface water, fossil fuels, land use

planning, … - would be most beneficial for the citizen, for the society, for the

environment and, particularly, for the interaction between all of them. It is

obvious here the relevance of ethical issues;

* earth-sciences education has to be prepared to argue

against the idea that socio-political and ethical criteria are not very much

relevant when one looks for a

solution to our current problems (see

the citizen responsibility about nuclear power and the ethics implications);

* earth-sciences approach cannot be internalist

anymore; it. Any consideration of the role of science should be carried out

within an externalist perception of the

society (see earthquakes and their consequences in the context of ethical perspectives) ).

* earth sciences is an area of knowledge enabling a

science teaching approach close to the utilitarian, economic, democratic and

cultural reasons and all of them

underlined by ethical perspectives (see

the radioactive wastes or the geological hazards).

One can think with a little bit more of details

about five great earth-sciences

curricular topics (at least in Portugal),

among many others, as good

examples of approaching which

enables articulation with ethical

concerns. These examples are as

follows: geological hazards, mineral resources, urban and rural planning,

environmental pollution and communication (Soares de Andrade 2001).

In this paper two examples are discussed in some

details, i.e. geological hazardous and urban and rural planning.

Geological

hazards -

the hazards arise through internal processes of the Earth (volcanic

eruptions, …) or by action of external processes (coastal erosion, landslides,

…). Coastal erosion is the most common geological hazard in Portugal. This event has consequences on the one hand

because of its frequency and one the

other hand taking into account the impact on small fishing communities and the

development of tourism along the coast.

The example of the Aveiro region is a

good one; every year, specially in

winter the media dramatically

report continuous assaults of the Atlantic Ocean on the coast line.

Let us think about a starting problem such as - will the Atlantic Ocean

eventually overcome all the artificial

protection barriers and destroy beaches

and settlements alongside the Aveiro coast?

From this point it is possible to design an approach

strategy, to develop with the students,

taking into account that the

irregular but progressive coastal

erosion is a consequence of natural factors (the last deglaciation) but also of

factors provoked by man (the building of hydroelectric dams, coastal engineering works,

the urbanization of dunes, …).

Geological processes are much more complex than they

seem at first glance, since they

work in interdependent ways and on variable spatial and temporal scales. When people react by

fighting , and not understanding, nature

the latter tends to restore the

balance. In time the result is mainly

disadvantageous to the human

aggressor.

In the classroom the teacher should be prepared to

include in the teaching and learning strategy as far as the topics like these

are concerned, an ethical reflection

about the responsibility of our

generation for the present and for the future as well. It is crucial to link the didactic approach of the

geological contents to a set of values and attitudes rather than to develop an

approach strictly rooted on the concepts themselves.

Regional

Planning – the rapid urban expansion of

Aveiro has raised serious problems related to factors having a significant

socio-economic relevance i.e. underground water supply, the exploitation of

mineral resources, the confinement of polluting substances, the conservation of

agricultural soils.

Thinking in earth-sciences curricular approach one can

face the students with questions such as: How is it possible to balance urban

expansion, and in general the economic development, with the preservation of

geo-environmental resources?

Information

provided by figure 1 is quite useful. In fact the region is situated

geologically in a small Cretaceous

basin with a monocline structure that

is slightly deep to the west. The sedimentary structure may be simplified as

follows: (i) underlying sediments: coarse-grained, permeable sandstones

(Cretaceous Coarse Sandstones); (ii) overlying sediments: fine grained,

practically impermeable mudstones

(Aveiro-Vagos clay).

Information

provided by figure 1 is quite useful. In fact the region is situated

geologically in a small Cretaceous

basin with a monocline structure that

is slightly deep to the west. The sedimentary structure may be simplified as

follows: (i) underlying sediments: coarse-grained, permeable sandstones

(Cretaceous Coarse Sandstones); (ii) overlying sediments: fine grained,

practically impermeable mudstones

(Aveiro-Vagos clay).

Fig. 2 Geological structure of Aveiro region (adapted

from Barbosa, 1996)

The Cretaceous coarse sandstones constitute the

water-bearing unit of the region (Cretaceous multi-aquifer) one of the best of

the Portuguese sedimentary basins. The recharge of the aquifer unit is practically impossible from the surface (in

vertical direction) due to the

relative impermeability of the overlying

ceramic unit; it is achieved in

an horizontal way from east, the aquifer unit outcrop and readily absorbs rain and river water. .

The inexorable expansion of the cities as well as the

expansion of the existing planned

industrial areas, constitute a real threat to the preservation of

hydrological resources. As far as the

hydrogeological unit is concerned, the recharge zone should allow an easy

infiltration of superficial waters; the planning of pine tree forests is a good

option.

Once more, in the classroom, teachers should define

teaching and learning strategies which enable the learner to understand that

for several reasons, but also for

ethical issues it is forbidden:

(i) urban and industrial developments that limit the superficial recharge of the aquifer; (ii) agricultural

procedures that may cause contamination

such as the over use of

fertilizers and pesticides.

Regional planning is traditionally assumed as a task

for geographers nevertheless, things are becoming more and more complex and

therefore they require a multidisciplinary approach and also the critical

attention of each citizen with an ethical perspective.

4. FINAL

COMMENTS

This is the broad context in which each citizen should

start to recognize first, and to understand next, the complexity of the science

social dimension. Science education plays here a crucial role strenghtening the

conscience of the learner. This means that types of teaching based on

replication, on teacher as an authoritarian didactic instructor and “fountains

of knowledge” (Thompson 2001) or on the contents themselves, without relations

to their social and cultural contexts, cannot be accepted. The learners are

citizens of the third millennium and, therefore, science teaching has to look

for something relevant which is happening i.e. the change of the science ethos.

The way the knowledge society uses science and

technology is a demanding one for the science education approach. This approach

implies an investigative perspective towards the development of competences by

the students, what means to change from a view of knowledge not relevant by

itself, to a knowledge in action. Action is synonymous with making decisions

and if the ethical issues were not also in the front line, in strong

articulation with science, there is no doubt about the weakness of the answers

to the problems one is faced with. In addition one needs to pay attention to

care for nature which concerns an

important ethical dimension in relation to the national and international focus

on education for a sustainable development. (Svennbeck, 2004).

Nevertheless, all the above requires a change both in

the scientists and the science teachers’ patterns. Scientists have, on the one

hand to become conscious of the part they play in producing certain knowledge

and products and the uses to which they are put, and, on the other hand, they

have to learn to view their work in the

context of values and goals that affect humanity. Science teachers have to

think that, what they do also depends on what is happening in the broad

society; in addition, they also should

achieve a wider vision of their purpose beyond the delivery of subject

knowledge. Science teachers are concerned with developing young people who

value for themselves. Values are

about self and one’s relation to other

people.

This means that ethical concerns should include an

attitude of reverence toward humans and other creatures, concern for the safety

of products and regard for them as possible impacts on the environment.

Earth-sciences education are very well placed to play here a relevant role, to work as guardian of planet

Earth; they should aim to influence

governments to adopt policies which sustain, rather than degrade, the

global environment. Earth-science educators have to co-operate with other

science professions, to contribute to a transnational education policy, and to

work towards a well-informed general

public which is a credit to a democratic society. This is the real

challenge for the 21st century!

Bibliography

Aikenhead, G. (2002). STS education. A rose by any other name. In Cross,

R. (Ed.). A Vision for Science Education.

London. Routledge Falmer. 59-75.

Barbosa, B. (1995). Implicações de estrutura geológica de Aveiro-Vagos no

planeamento regional e urbano. Porto, IGM.

Claxton, G. (1997). A 2020 vision of education. In Levinson, R. and Thomas , J. (Eds). Science Today. London. Routledge.

Frodeman, R. (2003). Geo-Logic.

Breaking Ground Between Philosophy and

the Earth Sciences. New York. State University Press.

Lee, Y. (2004). Science , Information and Ethics. TWAS, Newsletter,

16(2), 13-16.

Millar, R. (1996). Towards a science curriculum for public

understanding. School Science Review,

77(280), 7-18.

Osborne, J. (2000). Science for Citizenship. Monk, M. and Osborne, J.

(Eds.) In Good Practice in Science

Teaching. What Research has to say. London. Open University Press, 225-240.

Praia, J. e Cachapuz, A. (2005).

Ciência-Tecnologia- Sociedade: um compromisso ético. Revista

Ibero-Americana de Educación. (in press).

Sandal, R. (1998). Truth and scepticism. In The Social Science Bridge, Lisboa. Ministério da Ciência e

Tecnologia, 93-100.

Soares de Andrade, A. (2001). Problem solving in earth-sciences. In

Marques, L. and Praia, J. (Orgs.) Geoscience

in the Secondary School Curriculum. Aveiro, University of Aveiro285-298.

Svennbeck; M. (2004). Care for nature . In Wickenberg, P., Axelsson, H., Fritzén, L., Helldén, G. and Ohman,

J. (Eds.). Learning to change the world?

Swedish research on education & sustainable development. Lund.

Studentlitteratur, 21-31

Thomas, G. and Durant, J. (1987). Why should we promote the public understanding of science? In M.

Shortland (Ed.) Scientific Literacy

Papers. Oxford. Oxford Department of External Studies.

Thompson , D. (2001). Towards an earth-environmental science education

for all aged 4-16. In Marques, L. and

Praia, J. (Org.) Geoscience in the

Secondary School Curriculum. Aveiro. Universidade de Aveiro 299-332.

UNESCO (2001).World Commission on the ethics of scientific

knowledge and technology (COMMEST).

Sub-Commission on ethics of the Information society. Paris. UNESCO

Woodrock, N. (1995). Eart´s History as a Guide to the Eareth’s Future. In T. Wakeford & M. Walters (Eds.). Science

for Earth. London, J. Wiley & Sons, 173-194

Luis Marques* lmarques@dte.ua.pt