Satoshi Murao

Geological

Survey of Japan, AIST

CASM-Asia: a new initiative for artisanal mining in Asia

A new

international initiative for artisanal mining, “CASM-Asia“, was inaugurated as

a subgroup of the Community And Small Scale Mining initiative (CASM). The project is funded by the World Bank and

is coordinated by the Geological Survey of Japan, AIST.

The mission of

CASM is "to reduce poverty by supporting integrated sustainable

development of communities affected by or involved in artisanal and small-scale

mining in developing countries" and the CASM-Asia will follow this

concept. The aim of the project is to (i) identify, map and characterize

artisanal mining in Asia, (ii) share experiences and best practices to address

artisanal mining issues within the regional context, (iii) facilitate

partnerships for the implementation of improved development practices, (iv)

promote the formalization of the activities and a better contribution and

integration to local communities development and (v) aim at the sustainability

of the network through cooperation.

Since

artisanal mining issues include moral/ethics component, the CASM-Asia should

envisage whether it can contribute to the establishment of ethical principles

in addition to other protocols for management of artisanal mining.

Introduction

Artisanal

mining is an activity where poor people recover minerals as subsistence

activity with rudimentary tools and methods. It is often practiced in rural

areas of developing countries by those who lack the requisite education,

training, management skills and finance. The mining is often done in haphazard

manner with severe consequences to the environment, communities and miners

themselves. According to ILO (1999), there are about 6.7 to 7.2 million miners

in Asia and the Pacific region but not many information is available and

consequently not many cooperation among stakeholders are known in the region.

However the artisanal mining shows negative aspect as stated below, and its

approrpiate management is a pressing need of the region.

Artisanal/small-scale mining has a wide spectrum in

the kind of commodity, volume of production, number of engaged people, size of

business and social dimension. In some countries, indigenous people practices

artisanal mining as a part of their culture and such type of mining is called

“tradtional mining“. While artisanal mining without such cultural base can be

called “rush-type mining“. But whether a mining in a district belongs to the

concept of small, medium or large depends on the kind of commodity, deposit

type and other factors. Also sometimes both rush-type mining and traditional

mining are coexisting in the same area. Thus it is not easy to distinguish

artisanal, small-scale and medium-scale mining or rush-type and traditional

type of mining, and the definition of terms does not give practical convenience

to the discussion. In this paper, the word artisanal/small-scale mining is used

as an inclusive term to indicate mining conducted mainly by individuals or by

groups of individuals in developing countries. Junior mining companies are

excluded.

Problems

Artisanal mining has caused various kinds of problems in environmental,

accidental, health and social dimensions. Typical environmental issues are

deforestation, loss of vegetation cover, loss of soil, siltation of river,

heavy metal contamination of soil and sediments, water pollution, leak of

cyanide solution and industrial waste left on site. Geo-hazards are also often

observed like landslide after rain, flash flood/landslides, inundation by

water, gas explosion, earthquake, cave-in and mudslide after rain. Hazards in

the working environment are also known as dust, fume, noise, vibration, heat

and ergonomic problem. Health issue is another important category and HIV/Aids,

pneumoconiosis (silicosis) and heavy metal poisoning are examples. Accidents

often happen such as explosion of dynamite, elevator fall, man fall, oxygen

shortage, flooding after dynamite explosion and injury. Social issues are

complex and it is beyond the author’s ability but child labor, conflict between

local people and mining company, increase in crime and civil war to seize power

on mineral-rich land are well known to the public.

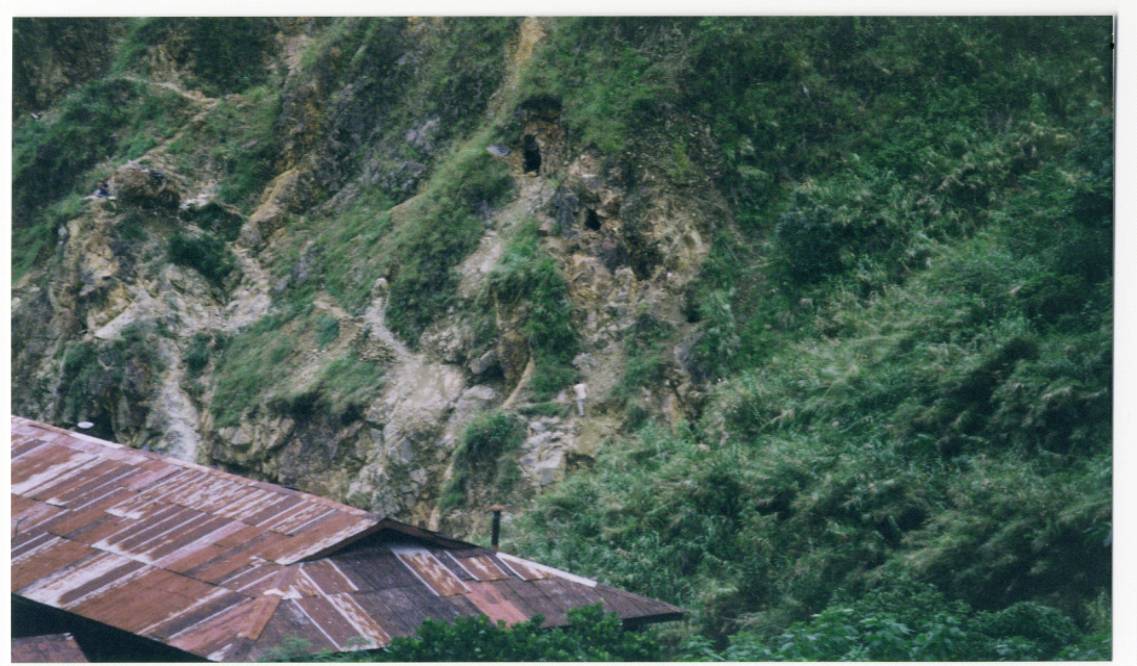

Fig. 1 Typical scene of artisanal mining with adits

(white arrows) opened on steep slope of mountain in the Philipines

CASM-Asia

In Asia, information on artisanal mining is very

scarce and mostly no cooperational network among stakeholders is known either

in national, regional or international scale. However it is an important

economic activity and is at the same time serious burden to the environment.

Thus the present author proposed a regional framework that designates

“CASM-Asia“. This is a subgroup of the “Community and Small Scale Mining

initiative (CASM)“ and is funded by the World Bank‘s Development Grant

Facility. The fund is deposited in the Coordinating Committee for Geoscience

Programmes for South and Southeast Asia (CCOP) and is coordinated by the

Geological Survey of Japan, AIST. The possible duration of the project is three

years.

The mission of CASM is "to reduce poverty by

supporting integrated sustainable development of communities affected by or

involved in artisanal and small-scale mining in developing countries (http://www.casmsite.org/about.html)"

and the CASM-Asia will follow this concept. The aim of CASM-Asia is to

(i) identify, map and characterize artisanal mining

in Asia,

(ii) share experiences and best practices to address

artisanal mining issues within the regional context,

(iii) facilitate partnerships for the implementation

of improved development practices,

(iv) promote the formalization of the activities and

a better contribution and integration to local communities development and

(v) aim at the sustainability of the network through

cooperation.

CCOP is an intergovernmental organization based on

Bangkok, and the mission is coordination between the member countries and

cooperating countries for the purpose of

(i) sharing information, knowledge, and best

practices,

(ii) coordinating and managing multi-national

projects on behalf of appropriate member countries, and

(iii) facilitating the partnership of projects

between cooperating countries and member countries and advising on

implementation strategies.

The specific

role of CCOP in fulfilling the objectives outlined above includes the

following.

Database construction on artisanal mining in Asia. The database archives

both technical and social information on artisanal mining, i.e., mineral

deposit geology, mineralization, target mineral, type of mining, environmental

degradation, incidents, related laws, rules and policy, and social issues.

Mapping each country to elucidate what commodity is recovered by whom and

where.

Goal Oriented Project Planning (GOPP) to understand important themes in

Asia. GOPP is an innovative tool for project management in which interactive

workshops involving all stakeholders in a project together with an external

moderator are held at different points in the project life cycle. GOPP aimsto

improve the quality of the analysis made by the group of partners in the design

phase of a project; o make the project more coherent and transparent by

clarifying the responsibilities of each partner; to provide trust and

self-confidence to project partners so to reduce the risk of lack of commitment

or failure during the implementation of the intervention; and to improve the

capacity of the group of partners to achieve more results in a limited time (http://www.gopp.org/gma/gmagopp.htm).

After completing the database, a GOPP workshop will be held in Bangkok in

order to know what themes should be prioritized in CASM-Asia project.

Setting-up web site and the link to

that of CASM and CASM-China.

Summarizing accumulated wisdom as “CASM-Asia vision“.

In the earlier stage, the project focuses on the

Member Countries except for China, Singapore and Japan (i.e., Cambodia,

Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, PNG, Thailand, Vietnam), and at later

stage, it will be expanded to countries outside of the CCOP region. Since the

artisanal mining issue in China shows a wide spectrum, it is hadled by another

subgroup CASM-China.

Guidlines of ASM

Since 1990s, a lot of endevour

has been done towards solutions of the artisanal mining issue, and best

practices have been observed and guidlines have been proposed. Since geoethical

code is a part of practical aspect of geoethics (Nemcova and Nemec, 2001), in

this chapter, previous guidelines related to artisanal/small-scale mining are

examined to see whether any ethic component is included and to consider how

CASM-Asia can reflect ethics in the activity.

One of the pioneering guides is

“Berlin Guidelines“ that includes proposals both for large-scale and

artisanal/small-scale mining (Mining Journal Books, 1992). The guidelines tries

to find assistance to better develope the small-scale mining and considers

(i) environmental issues,

(ii) regional beneficiation and purchasing,

(iii) co-operatives and private sector initiatives,

(iv) financial incentives,

(v) international and regional policies,

(vi) human resources development and technical co-operation. In the

discussion on the environment, the following statement is seen which shows

conditions for the environmental protection.

(On the environmental

protection) First, it will in most case be inevitable that adequate

preproduction environmental management plans for micro- and small-scale mining

are developed by the regional or national authorities or promotional agencies

related to the subsector (=artisanal/small-scale mining). Secondly, it

will be necessary to enhance awareness among small operators regarding their

responsibility towards the natural environment. Thridly, in

artisanal/microscale mining districts, the creation of legalized organizational

entities in the form of co-operatives, small operator associations or small

mining enterprises will be a pre-condition for a successful environmental

programme.

Unfortunately after the Berlin

Guidelines not many statements on morals are noticed among documents. For

example, a compedium on best practices of artisanal/small-scale mining

published by the UN Economic Comission for Africa (Economic Commission for

Africa, 2002) lists up the following items but not a concept of ethical

category.

Rationalization of artisanal and small-scale mining

Legal and regulatory framework

Financial services

Establishing formal marketing systems

Environmental management

Health and safety

Women and children issues

Institutional framework

Another standard is the Harare Guidlines by the

United Nations published in 1993 (see Labonne, 2002) to provide a framework for

encouraging development of small- and medium-scale mining as a legal and

sustainable activity in order to optimise its contribution to social and

economic development. Included are proposals for governments and their agencies

in the following six areas.

Legal

Financial

Commercial

Technical

Environmental

Social

The social area shows five guidelines as indicated below

that are in a sense related to ethics of mining activity. But they are

recommended to the governmental agencies and are not directly addressing to the

moral of people.

Governments and their agencies should endevour to the

best of their ability to:

a) While acknowledging the

realties of the small- and medium-scale mining sector in many countries, ensure

that employment and working conditions of miners do not fall below the

standards and norms set nationally and locally;

b) Ensure that health and safety for small-

and medium-scale mines do not fall below the standards and norms set nationally

and locally for all mines;

c) Ensure that medical, educational and other

services supplied to the bulk of the population are also made available to

small- and medium-scale miners;

d) Ensure that women working in the small-

and medium-scale mining secotr enjoy the same status, conditions and facilities

as their male counterparts and are not subject to indignities. Additionally

their earning capacity should not be disadvantaged by their added domestic

responsibilities;

e) The rights of exisiting groups are not

compromised by small- and medium-scale mining sector activity.

One of the latest discussion on the issue was held at

so-called “Yaounde seminor“ (UN ECA and UN DESA, 2002). It was a seminar on

artisanal and small-scale mining in Africa to identify best practices and to

build the sustainable livelihoods of communities held in Yaounde of Cameroon

(19-22 November, 2002). The meeting regarded artisanal/small-scale mining an

issue of poverty and recommended governments to integrate the policy for

artisanal/small-scale mining into the Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper process.

It offered a forum for debate between mining experts

and poverty reduction specialists to promote viable policies and realistic

implementation mechanisms. However it did not bring ethics to the agenda.

When it is focused on

artisanal diamond mining, the “Kimberley

Process“ (World Diamond Council, 2003) is well known as a scheme to stop

diamond revenues being used to fund wars and political violence across Africa.

The establishment of this scheme was motivated by people’s deep concern on

tragedic situation of some of the diamond-producing countries but the scheme

itself is a technical guidline and does not include ethic component.

Case study in the Philippines

From previous protocols and

guidelines, it is impossible to find clear provisions that contribute to the

geoethics. Thus the present author conducted some field survey as a precursor

to the CASM-Asia in order to understand the sentiment of artisanal and

small-scale miners. The projects were conducted in a mining area in northern

Luzon Island of the Philippines by an interdisciplinary team that includes

geologists and social scientists. The study area is a place of gold-rush type

mining and is known that it is already contaminated with mercury (Ministry of

the Environment, 2003). And it is very difficult to identify the wrongdoers for

the contamination because the study area has long been mined by large mining

company, artisanal miners (rush-type mining) and indigenous persons

(traditional mining).

In this area

a set of questionnaire sheets were distributed to local people (n=228) to ask

about their sentiment on mining and perception of risk. The sheets included

questions about risks and liablity on the on-going mercury contamination. The

questionnaire survey revealed that local people are hostile to large-scale

mining but not to artisanal mining; they regard mercury as dangerous material;

and they place artisanal mining neutral compared to other human activities such

as nuclear power plant. In other words, artisanal/small-scale mining is

acceptable to the local people. As for the liability on the mercury

contamination, the governmental

information dissemination to prevent the contamination was the most supported

idea, and local people’s action ranked only at 6th from the top among the

answers about countermeasures (Murao et al., 2003).

After the questionnaire survey, a meeting on

entrepreneurship (* International

Symposium, 2004) was conducted in Benguet,

Philippines, in March, 2004 to seek a

possibility to place ethical attitude as a part of their business moral. In the

meeting of entrepreneurship, a heated discussion was done on miner’s business

affairs such as gold buying program and insuarance but not a word was heard

about moral of mining . Main points in the meeting were as follows:

Micro-finance and insurance

Contract mine operation

Barangay microbusiness enterprises

Gold buying program by bank

Requirments of registration of mining cooperatives

Traditional mining in the Philippines

In the Philippines, contrasting to the gold-rush type

mining, traditional mining by indigenous people is seen as a part of their

culture. Typical case is seen in northern part of Luzon Island. The traditional

mining has been practiced by indigenous groups “Kankana-ey“ and “Ibaloy“ for

nearly 400 years (Liyo, 2002). Miners have a practice called “ngilin“ where

whole community abstains from working in the tunnels to ward off sickness and

to avert bad luck while mining (Caballero, 1996). Also they have traditional

sharing system “sagaok“ and “makilinang“ in which children, women and old persons

can get share of ore and the tailings respectively. Taboos with them are

stealing ore; eating the meat of dogs, cows and goat before working in the

mines; eating foods with fishy smell; eating foods containing ginger; and other

foods that are offered in canao or ngilin; being drunk inside the mines;

flirting; laughing; singing; shouting; crying or showing of other hysterical

emotions inside the mines; burning of clothes inside the abucay; not consulting

the elders about bad dreams; wearing indecent clothes; entering tunnels when

there is canao, ngilin, death in the family and other traditional events in the

community (Domalsin, 2002). These codes are considered to maintain the peace

and order of the local community but they seem to be applied only within the

community and are not extended towards the world outside.

Conclusion

Artisanal and

small-scale mining is typically practiced in the poorest and most remote rural

areas by a largely itinerant, poorly educated populace, men, and women with few

employment alternatives. In such

circumstance, it is very difficult to draw people’s attention to the moral

issues. Consequently little attention has

been paid for the moral norm although tremendous amount of efforts were done to

protect the environment and people. Artisanal miners themselves do not pay much

attention to the moral either.

It is necessary to establish geoethics applicable to the artisanal mining

and to bring them down to the public. It is also necessary to establish

influential frameworks to achieve the goal. Such framework can be

international, national, regional, or local depending on issue and problem. The

CASM-Asia can be an option to introduce geoethics to the stakeholders of

artisanal/small-scale mining.

For the specification of the work, indigenous

people’s wisdome mentioned above can be a seed to introduce ethical components

to the protocols of artisanal mining.

But for the moment, it lacks

sense of global partnership that is becoming common in the world and is

typically stated in the preamble of the “Earth Charter“ (http://www.earthcharter.org): “We must decide to live with a sense

of universal responsibility, identifying ourselves with the whole Earth

community as well as our local communities. We are at once citizens of different

nations and of one world in which the local and global are linked. Everyone

shares responsibility for the present and future well-being of the human family

and the larger living world.“

In conclusion, linkage between local wisdom and global experience seems

to be vital in finding solutions of the artisanal mining issue.

Acknowledgements

The following

organizations provided research fund to the author for artisanal mining study:

former Ministry of International Trade and Industry (Japan, presently METI),

Ministry of the Environment (Japan), Research Institute of Economy, Trade and

Industry (Japan), and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

References

Caballero, E. J. (1996): Gold from the Gods: Traditional Small-Scale

Miners in the Philippines, Giraffe Books, Manila, 263pp.

Domalsin, C. (2002): Kabunian’s gold in the last frontier, In:

Murao, Maglambayan, De La Cruz (edts), Small Scale Mining in Asia: Observations

Towards a Solution of the Issue, 51-54, Mining Journal Books, London.

Economic Commision for Africa, UN (2002): Compedium on

Best Practices in Small-Scale Mining in Africa, Addis Ababa, 101 pp.

ILO (1999): Social

and Labour Issues in Small-scale Mines, Report for discussion at the Tripartie

Meeting on Social and Labour Issues in Small-scale Mines, Geneva, 17-21 May

1999.

* International Symposium on the Diversity of mining and Sustainable

Development: A Meeting to Study the Business Practices of Small-Scale Gold

Mining in Benguet, Philippines. March 17, 2004, Baguio, Philippines.

Labonne, B. (2002): Harare Guidlines, In: Murao, Maglambayan, De

La Cruz (edts), Small Scale Mining in Asia: Observations Towards a Solution of

the Issue, 57-62, Mining Journal Books, London.

Liyo, N. S. (2002): Traditional versus gold-rush type small-scale mining,

In: Murao, Maglambayan, De La Cruz (edts), Small Scale Mining in Asia:

Observations Towards a Solution of the Issue, 55-56, Mining Journal Books,

London.

Mining Journal Books (1992): Mining and the Environment,

the Berlin Guidelines, 179pp, London.

Ministry of the Environment (2003): Interdisciplinary Study on

Environmental Management, Planning and Risk Communication in Gold Rush Regions,

Tokyo, 75pp.

Murao, S., Kikkawa, T., Takemura, K., Maglambayan, V.B. and Bugnosen, E.

(2003): Project Report of the Research on Risk Communication Necessary for

Mineral Development Programs, AIST 03-C-00008, Tsukuba, Japan, 225pp.

Nemcova, L. and Nemec V. (2001): Spirituarity and geoethics, In:

Spirituarity in Management, 66-72, Szeged, Hungary, July 1-3, 2001.

UN ECA (Economic Comission of Africa) and UN DESA

(Department for Economic and Social Affairs) (2002): Seminar on Artisanal &

Small-Scale Mining in Africa: Identifying Best Practices & Building the

Sustainable Livelihoods of Communities, Recommendations, Yaounde, Cameroon.

World Diamond Council (2003): The Essential Guide to Implementing the

Kimberley Process, NY.

* * * * *

Dr Satoshi Murao

Scientific Director, Geological Survey of Japan, AIST

Higashi 1-1, AIST No.7, Tsukuba, Japan 305-8567

TEL:+81-298-61-2402; FAX:+81-298-56-4989, E-mail: s.murao@aist.go.jp